Open-ended questions can be great conversation starters for social and workplace situations. Unlike closed-ended questions, which only yield one-word answers, open-ended questions get people talking. Mediators rely on open-ended questions, as they are powerful active listening tools, essential for effectively navigating conflicts. Most importantly, they help to engage and empower people to respond in their own words.

To be effective, open-ended questions should start with who, what, when, where or how.

You will notice, I also left “why” off this list, because it can often sound leading and judgemental, putting the speaker on the defensive. The goal for mediators in using open-ended questions is simply to listen.

We encourage participants in our mediation courses to begin their questions with “what” and “how” as often as possible. Mediators avoid starting questions with “do you” or “will you” or “can you” as these lead to closed-ended, yes or no, answers.

To actively listen, we must invite the speaker to say more, not less. Open-ended questions are powerful in this regard.

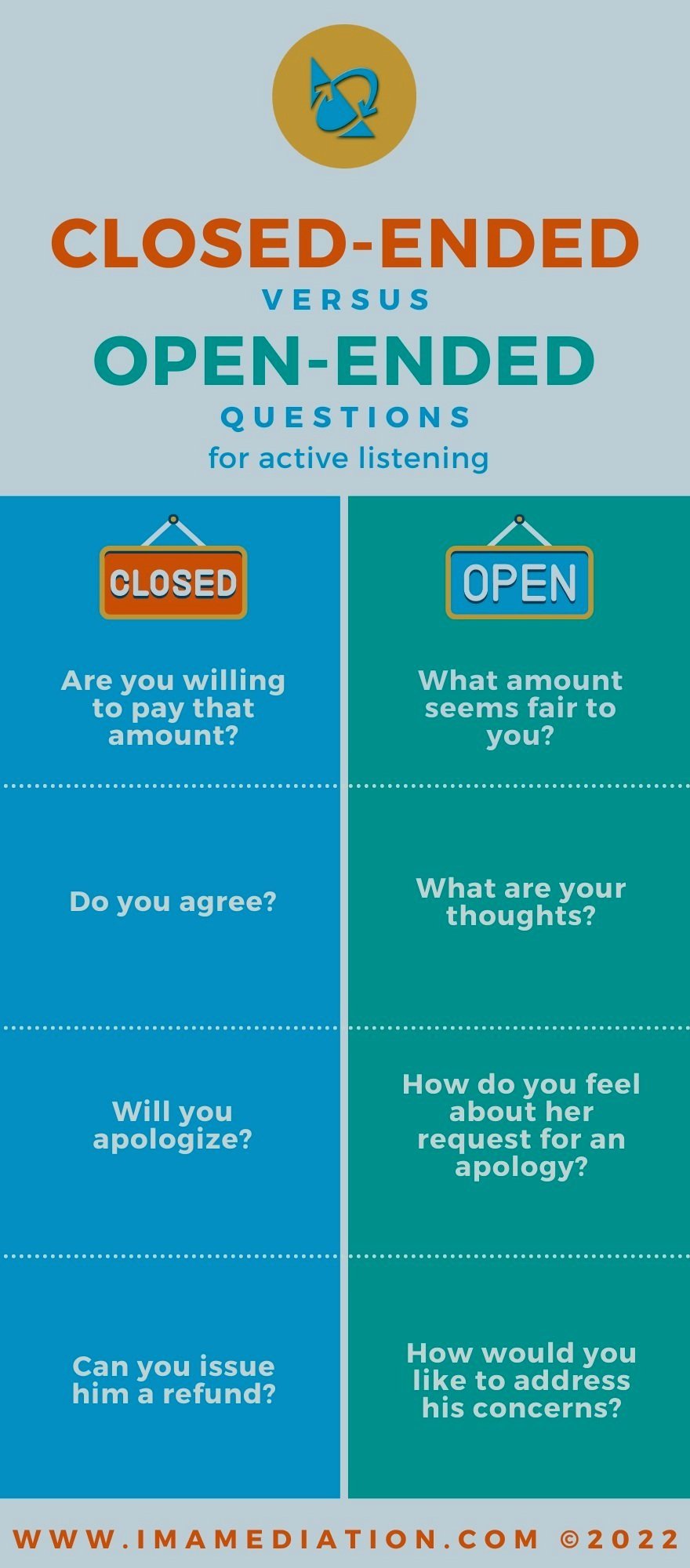

Take a look at the infographic on the right and you can see what I mean. On the left column, you see closed-ended questions that can only be answered with one-word responses. The right column, on the other hand, asks the speaker to share broader responses.

Open-ended questions are often harder to craft than closed-ended questions, but essential for active listening.

I’ll be the first to admit, active listening hasn’t always come naturally to me.

THE POWER OF OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS

Even though I had discovered the value of open-ended questions as a mediator, well before my sons were born, I will admit to you right here in the open, I neglected to use them effectively at home. In fact, I learned the hard way that closed-ended questions were conversation stoppers. When my three sons (now in their 20s) were just starting elementary school, I struggled to get more than a mumbled word or two out of them.

Like many parents, conversations with my kids often went like this:

Me: Was school good today?

Son: No. [makes a face]

Me: Did you eat your lunch?

Son: M-hm.

Me: Do you have homework?

Son: [shrugs shoulders, loses interest].

When someone responds with one-word answers, the conversation ends pretty abruptly. The reality is, closed-ended questions are leading questions. We are not actively listening when we use them.

Eventually, I realized I could get my sons to open up by using creative open-ended questions to anticipate what they’d be willing to share with me. Once I tapped into those questions mediators use to encourage parties to open up, conversations with my sons went more like this:

Me: Who did you sit by today at lunch?

Son: Dillon and Jakob. Dillon always has lunchables. He likes to trade with me. [Smiles] Thanks for putting applesauce in my lunchbox, Mom! But…[sigh]...could you not put those smiley face notes in my lunchbox anymore, please?

Me: Oh, sorry, what happened?

Son: Nothing happened. It’s just embarrassing. I know you love me, Mom, [smile] you don’t need to give me notes every day.

Me: Ok. No problem, I won’t put them in every day, but it makes me feel good to send you notes to let you know I’m thinking of you. How about I surprise you?

Son: Sure, maybe on Fridays, because Dillon always gets the school lunch on those days and he won’t see when I open my lunchbox.

Me: Great idea!

Me: [Moving on…] What games did you play during recess today?

Son: Oh, it was really fun today! We played flag football and guess who was one of the captains? [Smiling]

Me: Wow! What does the captain do?

Son: [Sits down and tells me all about the game, who he picked for his team, etc.]

It’s funny that I can recall that conversation like it was yesterday. Using open-ended questions in my living laboratory at home not only helped me be a better listener, but I also felt more connected with my children. By being a better listener, I was cultivating respect in our family. I realized first-hand that listening is one of the greatest gifts we can offer others.

With kids (as with adults), one needs to be strategic about the right questions to get them to open up. This is a frequent topic in our mediation courses.

OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS MEDIATORS USE

In my work -- spoiler alert for new clients -- here are five open-ended questions I most frequently use in mediation sessions, although not necessarily in this order.

What brought us here today?

By asking this question, I let the parties know I really want them to unveil, in their own words, the stories they bring to the table of what led them to mediation.

This is quite often the first question I ask clients after my mediator’s opening statement, in which we’ve discussed my role, the mediation process, confidentiality and other boilerplate information. Because I mediate in either the facilitative or transformative frameworks (discussed in greater detail in our mediation courses), I don’t ask parties for summary statements in advance of the mediation. Whenever possible, I like to start with somewhat of a blank slate, hearing first-hand from the parties why we are in mediation.

You’ll notice I also leave out the word “conflict” in this question. I learned the hard way that if I suggest to the parties that they are in mediation because of a “dispute” or “conflict” I will actually exacerbate the friction. Not only are most people resentful for being at the mediation table, they believe they wouldn’t be there if not for the other party involved. In other words, suggesting “conflict” implicates both parties and neither one really wants to take the “blame.” Asking what brought us together is much easier to answer, because they can both agree on at least some of the reasons they scheduled a mediation, and those reasons may be more positive, such as “I want a resolution” or “I want answers” or “I just want this to go away.”

By asking this question in such a broad way, I let disputants explain their perceptions of how we got here. As a mediator, I try my best to look at the situation through each party's view of the conflict. I imagine a glass prism is separating them and each one sees the conflict through that same prism. When I step to Paul’s side it’s clear to me why he sees purple, and yet, when I step to Fabiola’s side, it’s obvious to me why she sees green, metaphorically-speaking.

Let me share an example from a case I mediated long ago between a supervisor, I’ll call Fabiola, and an employee, I’ll call Paul.

Paul felt like his boss, Fabiola, didn’t trust him because she kept watching his every move. He was under a tremendous amount of pressure at home due to a sick child. He had limited child care options and needed to coordinate with family throughout the day. He also knew Fabiola didn't want personal issues to get in the way of the workplace.

Fabiola, on the other hand, asked the entire team to be fully present at meetings and put all devices on silent mode. It appeared to Fabiola that Paul was being insubordinate, because he was constantly looking down at his phone and responding to messages when other team members were trying to speak. He just didn’t bring the same drive and enthusiasm he had when she first hired him. Paul ignored Fabiola’s emails. When she finally confronted him face-to-face, he got defensive. She wanted them to work with a mediator, so they could safely open up about what was going on between them.

In that case, both parties experienced the same conflict, but their unique experiences shaped how they perceived it. When I asked these parties the question of what brought us here today, they openly and honestly explained their concerns, from their respective vantage points. The funny thing is that it did not take long for each of them to see how they got to the mediation table.

Fabiola realized she had not conveyed empathy to employees who had family matters to resolve. She also wanted to let Paul know she valued him as an employee. Paul realized Fabiola wasn’t singling him out, she just needed his undivided attention at key meetings. This was the “how we got here” and because they opened up so quickly to this question, they also mutually recognized options for resolving it, which they did, eventually.

What would you like to see happen?

This question helps the parties begin to explore their interests.

Too often, in conflict we have no idea what we are seeking. Until we can explore those issues hovering below the conflict iceberg, the negotiation is rather unproductive.

Instead of focusing on interests, parties will make demands, based on their positions.

They’ll say things like:

“You owe me.”

“You never consider my needs.”

“I’m not budging.”

“What you did was wrong.”

“On principle, I will not give you a dime.”

“This workplace is toxic.”

“You are intimidating.”

“Everyone knows that kind of behavior is intolerable.”

“I’ll never trust you again.”

To shift the parties into engaging proactively toward a resolution, I ask this question, “What would you like to see happen?” It encourages them to consider their real needs. Often, when prompted to think about interests, parties will eventually discover what they really want is something along the lines of:

Compensation for damages

Public acknowledgement of an injustice

An apology

Reconciliation

Termination of the relationship

To save face

Validation of hurt feelings

An explanation

Improved communication

Boundaries

A healthier work environment

Recognition of accomplishments

To better understand the best and worst possible outcomes

An end to the stress caused by the conflict

It can take quite a bit of time for parties to figure out what their respective interests are, let alone put them out on the table for discussion, but once they do, they can focus on more realistic actionables and plans. Eventually, each person needs to talk about what he or she is or isn’t willing to do to resolve the conflict.

Parties can begin to shift from discussing their positions to negotiating on their interests when a mediator asks, “What would you like to see happen?” At a minimum, they have a better understanding of what the other person seeks. They can shift from simply telling the story of the past that led them here to illuminating possibilities in the future.

What would your life be like if this conflict went away?

It’s tempting sometimes to give advice to the parties, such as, “Just move on, is it really worth all this pain and anger?” As a third party interventionist, even after decades of practice, seeing parties remain stuck in their positions can be challenging.

As a mediator, however, I follow a code of conduct that enables parties to find their unique solutions, and this question opens the door to self-determination, one of the promises of mediation.

Asking this question can feel risky, as it opens some parties up to be vulnerable. Emotions flow, which makes some people feel uncomfortable.

On the other hand, this question is often a springboard for empathy, reconciliation and letting go. It invites the parties to imagine the future. By doing so, parties begin to wonder what is holding them back from a resolution. This can be pivotal to the negotiation. Parties begin to transition the focus from negativity of the past to co-creating a better future.

Asking parties to imagine life without the conflict helps them to explore the “why” of their future relationship a little further. Instead of focusing on blame and lines in the sand, they shift into problem-solving mode.

Most often, at least one person will pause, think for a moment and respond with something along the lines of, “I really just want to put this behind me.”

Sometimes, that statement is enough to release the tension between the parties. When one party states they just want out of the conflict, it can actually feel like a concession. It is often also a shared interest. Instead of communicating, “I want to win at all costs'' they can now focus on, “How can I move forward, without this conflict?”

Imagining their conflict-free future empowers each party to consider the costs of staying entangled in this undesirable situation versus moving forward. One or both parties’ desire to let go is typically palpable from this point forward. They not only see the conflict from a new perspective, they see their interdependence differently. They may begin to wonder what the conflict is really about, as I wrote about in a previous article, and whether it’s worth remaining stuck in it.

Moving from discussing positions to exploring mutual interests shifts the parties from stalemate to negotiation. That doesn’t mean the conflict is over, they are just beginning to bargain with one another.

Another way I may ask this is inspired by How to Talk So Kids Will Listen & Listen So Kids Will Talk, “If you had the magic powers to resolve this, what might that look like?” I have found asking the question in this way, with some parties, can lighten the air a bit and nudge them to think creatively. It also helps them to feel more in control of their future, which can enhance peacebuilding.

What can you offer?

The best way to really ask this question is more like, “How might you be able to satisfy the other party’s interests?” This doesn’t mean a tit-for-tat or even a compromise. Instead, it’s an invitation to listen to one another and review their respective interests. Negotiating over interests then becomes possible.

I try to ask each person in the mediation to explore what the other party is seeking and brainstorm options to make it work.

If each party wants to get unstuck, they need to consider what role they can play in moving forward. This doesn’t always mean giving in. It also does not mean giving anything up. This is a gentle reality-testing question which essentially nudges the parties to consider the cost of staying in the conflict versus moving forward.

By asking each party what they can offer, they may also discover limitations, both tangible and intangible.

For example, when I was going through a divorce (years ago) in our mediation, I asked for – no, I demanded – an apology. From my perspective, he owed me one: I had supported him throughout medical school, and right before I was to start law school, he ran off with a younger woman, leaving behind our three preschoolers and me. I was both traumatized and stuck in my state of victimhood. I wanted him to recognize my pain. I begged for acknowledgement of my suffering and refused to participate in negotiations until he apologized.

At first, the mediator ignored my request for an apology, which further infuriated me. I kept repeating myself, until the mediator finally asked me what it would take for me to move onto another issue. I told her I did not want to discuss practical issues, such as child support and parenting time, until we addressed how, from my perspective, he had hurt me and ruined our family.

She turned to him, “So, you heard what Kate said. She wants you to apologize.”

He looked me straight in the eye, shrugged and gave a deadpan response, “For what?”

I can still remember the sting I felt when I heard those words. That dose of reality also dashed my hopes of receiving the apology I felt I deserved.

In reality, what I was offering him was a huge heap of guilt. I wanted him to suffer, and he wasn’t having it.

The mediator returned to me and sighed, “Your need for an apology is understandable. But, at this point, I think if you asked him for $1 million, you’d stand a better chance of getting what you wanted. Does this help you understand where we are now?”

Honestly, it did. I realized at that moment, like the mediator’s “million dollar request” analogy, he did not have it in him to meet me where I was or to hear what I was requesting. The epiphany for me was that forgiveness and apologies can be transactional, and I couldn’t ask for more than he was capable of giving.

The mediator then asked each of us what we could offer one another. At that point, I realized I had to meet him where he was and negotiate from that point, or we would stay locked in a toxic battle or -- even worse -- we could spend more time and money to have our future decided by a judge.

Asking the parties what they can offer to one another can spark connection, empathy and creativity. It also gives each person an opportunity to explore what is doable. A good mediator also gives permission to each party to draw lines in the sand, so they do not feel exploited or pressured. Moreover, the parties should not feel coerced into compromising, but rather considering solutions from a fresh angle and seeing what, if anything, they can do for one another in order to move forward.

The aim of mediation is not finding perfection or happiness, but agreement on something they can both live with, that is better than the mire in which they’ve been stuck.

What resolution can you live with?

Once the parties begin to explore their respective interests, typically at least one of them has considered what they can do to transform the conflict. It is not unusual for one of the parties to offer a game-changing resolution before I even ask this question.

Even a small concession can have a powerful and transformational impact on their negotiation.

If parties are not quite ready to propose resolutions, I may review some of their partial agreements, so they recognize the progress they have made. Pointing out even their small victories can build parties’ confidence in their ability to keep the momentum going.

For all sorts of reasons, sometimes no one is willing to talk about a resolution. As mediators, we remind ourselves, they are still participating in the mediation, so we know they are there for a reason and not at an impasse. At that point, I may follow up with a reframed version of this question, “How much does staying in this conflict mean to you?”

With my fingers, I often draw an imaginary box in the air and tell the parties, “Let’s pretend that every issue and resolution we are realistically dealing with is inside this box. Everything outside this box is not doable, based on what you have each told me.” That imagery sometimes enables them to answer the question, “What resolution can you live with?”

It’s a gentle nudge that encourages them to operate in reality. It may also be an opportunity to explore the BATNA, or best alternative to a negotiated agreement, or what may result if they don’t reach a resolution.

Occasionally, mediators can move the parties forward by highlighting their temporary or partial resolutions, versus focusing on resolving every issue on the table. After over 25 years in this field, I have learned that “resolution” does not necessarily mean closure. Sometimes, in order to move toward a more harmonious future, we either need to reframe our perspective or accept those things we can’t change.

OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS FOR ACTIVE LISTENING

The timing, tone and framing of these five questions -- and any open-ended questions -- needs to be managed, for them to be effective. There are also some powerful self-reflective questions mediators should consider, to remove barriers to communication.

As I mentioned earlier, you will notice each of these powerful questions do not begin with the words “do,” “will,” “can” or “are.”

Why not? Well, starting with those words leads to closed-ended questions.

When you find yourself beginning to form a closed-ended question, your best bet is to reboot it by starting with “What…” or “How…” In most cases, you will most likely be able to easily craft an open-ended question. If you struggle to find the right question, you can’t go wrong by saying, “Tell me more about that.” That phrase can not only convey that you are listening, it may also buy you some time to come up with a powerful “what” or “how” question to engage your active listening skills.

In one of our recent webinars, our Master Mediators brainstormed open-ended questions they have found useful. You can access that list, and more, in a workbook we created. It can be used as a cheat sheet or as inspiration to add your own open-ended questions.

How will you use these five powerful open-ended questions the next time you are called upon to actively listen? Drop your comments below!